Intracranial hemorrhage (bleeding), or apoplexy, comprises about one tenth of all acute cerebrovascular illness. Regardless of cause, intracranial hemorrhage is a serious illness with a high rate of mortality. At the bedside the physician can only suspect the diagnosis, which must be confirmed by finding blood in the cerebrospinal fluid or by the demonstration of a hematoma at surgery. The causes of intracranial hemorrhage are numerous, and the clinical pictures are similar regardless of the cause. It helps one to understand the clinical problem better if one remembers that nontraumatic bleeding within the cranium takes one of four separate anatomic courses and that these produce three relatively distinct clinical pictures:

- Bleeding emanating from vessels on the surface of the brain and limited to the cerebrospinal fluid-filled space between the pial and arachnoid membranes is called subarachnoid hemorrhage.

- Subarachnoid hemorrhage with intracerebral extension occurs when the sudden force of bleeding from a surface vessel also penetrates into the brain itself; signs and symptoms of both the subarachnoid and the parenchymal lesions result.

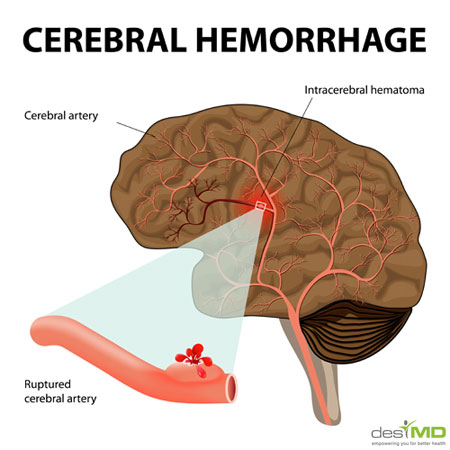

- Bleeding from ruptured vessels within the substance of the brain is called intracerebral hemorrhage. This may remain isolated therein as a cerebral hematoma.

Intracerebral hemorrhage may extend through brain tissue to the ventricles or subarachnoid space, causing signs and symptoms of both the parenchymal and the subarachnoid lesions.

ETIOLOGY

Bleeding from ruptured arteries is the usual source of intracranial hemorrhage although veins also may bleed. The accompanying table lists the common causes.

Arterial Aneurysms

Berry Aneurysms. These are small, round, or saccular, berry-shaped dilatations that form characteristically at arterial bifurcations at or near the circle of Willis. Their cause is uncertain, for aneurysms are not familial and they are rarely found in infants. They arise, however, from what are thought to be congenital defects in the media of cerebral vessels. The wall of an aneurysm is thin, composed usually only of intima and subintimal connective tissue. Muscle or elastic tissues may be evident at the origin of the aneurysmal sac from its parent vessel, but these tissues thin out and disappear as the sac enlarges. Most aneurysms are less than 1 cm. in diameter; a few, however, dilate to as much as 2 to 5 cm. As the aneurysm enlarges, it may develop a narrow neck or may remain broadly attached to the vessel wall.

CAUSES OF INTRACRANIAL HEMORRHAGE

- Arterial aneurysms

- “Congenital” berry aneurysms

- Acquired arterial aneurysms

(1) Fusiform aneurysms (21 Mycotic aneurysms

- Arteriovenous (A-V) anomalies

- Hypertensive vascular disease

- Vascular lesions associated with primary or metastatic brain tumors

- Systemic bleeding diathesis

- Undetermined and miscellaneous causes

Most berry aneurysms, approximately 85 per cent, develop around the anterior portion of the circle of Willis, arising from the internal carotid, the posterior communicating, the middle cerebral, the anterior communicating, or the anterior cerebral artery, as shown in Figure 8. The most common site is the point of junction of the posterior communicating artery and the internal carotid. About 15 per cent of aneurysms arise from the vertebrobasilar artery system. Multiple aneurysms are found in about one of every six patients. Not all aneurysms bleed, and some are found incidentally at postmortem examination. Occasionally, they become so large that they compress adjacent cerebral tissue or cranial nerves, and, rarely, they enlarge sufficiently to cause a clinical state that simulates brain tumor.

What makes an aneurysm rupture at any given

- Internal carotid artery.

- Anterior communicating artery.

- Anterior cerebral artery Middle cerebral artery Posterior communicating artery Posterior cerebral artery Superior, cerebellar artery Paramedian arteries Circumferential arter.

- Anterior inferior cerebellar artery Basilar artery Vertebral artery

- Posterior inferior cerebellar artery Anterior spinAL artery worse. However, some surgeons still believe that, in properly selected patients, surgical correction of an aneurysm of the anterior cerebral or anterior communicating artery is beneficial.

The outcome of surgical treatment of middle cerebral artery aneurysms is more uncertain. In the controlled treatment series, direct surgical attack provided better results in male patients, whereas women with middle cerebral aneurysms fared less well with surgery than when treated conservatively. The explanation of this difference appears to be that women are more prone to cerebral infarction after surgery than men. In addition, women have smaller, more fragile, aneurysms that make surgery more difficult.

Aneurysms on the vertebrobasilar vascular tree are difficult to reach surgically. The most successful surgery reported has been for aneurysms -arising from the vertebral artery near the branching of the posterior inferior cerebellar artery.

Current surgical techniques include a large number of methods for dealing with ruptured aneurysms. Most of the carefully controlled treatment trials have utilized either common carotid ligation or clipping or tying of the neck of the aneurysm or its feeding vessels. To reinforce the aneurysm and prevent recurrent bleeding, plastic coating arid gauze wrapping have been utilized, but their superiority over other methods of surgical treatment has yet to be proved.

If the patient is not suitable for surgical treatment or if surgery must be delayed, a program of medical treatment should be instituted as outlined above.

Arteriovenous Anomaly.

Surgery for A-V anomalies requires the tying of feeding vessels or the amputation of a portion of the brain containing the anomaly. The latter treatment is curative if the whole A-V malformation can be removed, but it is limited to those instances in which the anomaly lies entirely in or on the occipital pole or the frontal pole. The chance of neurologic disability associated with removal of A-V anomalies in other sites is usually too great to justify surgical therapy unless major disability had been present before bleeding.

Ligation of vessels feeding the anomaly has been recommended, but no carefully controlled evaluation of this form of surgical therapy has been done. Carotid ligation to reduce the blood pressure in the anomaly is also believed to reduce the chance of recurrent bleeding. Recently, artificial embolization with plastic spheres introduced into the feeding arteries has been reported to be successful in obliterating the anomaly.

Fortunately, the chance of recurrent bleeding with arteriovenous anomalies is less than with aneurysm. Also, bleeding carries a relatively low mortality, so that for most patients with arteriovenous anomaly and intracranial hemorrhage, medical management identical to that described for ruptured* aneurysm is the treatment of choice. The frequency of disability and mortality associated with surgical treatment are too high to justify its use except in highly special instances. Convulsive seizures are common with arteriovenous anomalies and should be treated with anticonvulsants as outlined in the article on Epilepsy.

Intracerebral Hemorrhage Treatment.

Cerebral hemorrhage is a severe disease and one for which there is no satisfactory form of treatment. The immediate medical treatment was outlined in the introduction to this article. It must include meticulous attention to the problems imposed by impaired consciousness and abrupt neurologic disability.

Whether and when to operate on cerebral hemorrhage is a recurrent question, and efforts have been made in this direction for years, although generally with poor results. Recently, McKissock and his colleagues in England carried out a carefully controlled evaluation of surgical treatment of acute cerebral hemorrhage due to hypertensive disease, in which they showed that patients treated surgically fared less well than those treated conservatively. No matter what the treatment, patients in deep stupor or coma from intracerebral hemorrhage rarely survive. For patients who survive the initial cerebral insult and become stable clinically, removal of a persistent encapsulated hematoma may lessen neurologic disability and hasten improvement.

Causes of Intracranial hemorrhage

Surgical removal of an intracerebral hematoma caused by bleeding from a ruptured aneurysm has been no more encouraging than when hypertensive vascular disease causes the hemorrhage. Patients with intracerebral hematoma from ruptured aneurysm are usually in coma and have severe neurologic dysfunction; survival in these circumstances is unlikely.

Removal of an intracerebral hematoma caused by bleeding from a ruptured A-V anomaly has been recommended for patients with neurologic disability. The results are difficult to appraise objectively, but surgical treatment has its best chance of offering relief if the patients have become stable clinically and have a well localized, encapsulated hematoma causing symptoms and signs of a mass lesion.

Patients who recover from intracerebral hemorrhage should begin programs of rehabilitation as soon as the effects of acute brain damage have subsided. Such a program begins with passive exercise of the paretic extremities to help avoid contractures and progresses to active exercises as voluntary movement returns. The program is as outlined in the discussion of cerebral infarction.