Tuberculous meningitis is the most serious form of tuberculous infection, invariably fatal when untreated, and responsible for a large portion of the tuberculosis deaths in infants.It was Colon regarded as primarily a disease of very young children, but at present half or more of the cases are observed in adults. It remains a dread disease because of the permanent and often incapacitating neurological damage that may occur, particularly : n the very young, even with prompt diagnosis and 1 therapy.

Clinical Features and Diagnosis.

The course of the illness may vary from abrupt and severe, resembling acute bacterial meningitis, to subtle and chronic, extending over several months. In some, instances slowly developing defects in mentation or affect may dominate the picture, with little to suggest either meningitis or infection.he majority of untreated cases. This is not due to implantation, however, as the memxigelemselves quite resistant to blood-borae mfec- ition. Rather, the infection reaches the subarads- oid space by direct extension from a sobparem uberculous focus, most frequently a snail. pendymal tubercle at or near the surface of the rain.

Less frequently, larger tuberculomas may reach the subarachnoid space. Direct extension from a larger parameningeal focus in the spine, middle ear, or elsewhere may also rarely occur. The fact that meningeal infection occurs by direct extension from adjacent foci explains the observation that meningitis may develop several weeks or months after overt miliary tuberculosis.

Also, as the critical factor is location, the extent of the bacteremia merely enhances the probability of meningeal involvement, which may occur as a consequence of a small, transient, and otherwise inapparent hematogenous phase. As in miliary disease, the seeding focus in infants is usually the primary parenchymal-hilar node complex, and in adults a chronic, extrapulmonary, and often clinically latent focus is usually responsible Once infectious material gains access to the sub- arachnoid space in the hypersensitive host, an allergic inflammatory response develops, and me infection is spread via the cerebrospinal nuid. resulting in secondary implantation of bacilli elsewhere on the meningeal surfaces.

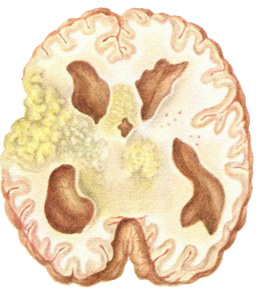

Anatomic and physiologic factors concerning the fiow and pooling of subarachnoid fluid result in maximal involvement at the base of the brain, where the exudate may become grossly thickened, collagenous* or caseous, assuming the characteristics of a space-occupying mass and causing pressure injury to neighboring cranial nerves and long tracts. Obstruction of the foramina at the base of the brain may produce obstruction to the flow of cerebrospinal fluid and hydrocephalus. Involvement of the vasculature often produces thrombosis and ischemic brain damage.

Extra meningeal tuberculosis is clinically apparent in approximately half the patients and the tuberculin test is positive in over three fourths. but the absence of both does not exclude the diagnosis. A variety of neurological abnormalities may be present or develop, including cranial nerve palsies, blindness, deafness, long tract signs, arachnophobia block, and disorders of consciousness ranging from mild confusion to dementia or coma.

Cerebrospinal fluid pleocytosis with over 50 per cent mononuclear cells is the rule. Cell counts are rarely over 1000 per cubic millimeter, more frequently in the 50 to 200 range, and may be as low “s only a few lymphocytes. Patients with acute

and severe symptoms may demonstrate a high and predominantly polymorphonuclear cerebrospinal fluid cell content early in the course, causing confusion with bacterial meningitis. The cerebrospinal fluid protein concentration is almost always elevated, and the glucose content is usually depressed in comparison with simultaneously determined blood glucose. Smears of the sediment will reveal acid-fast bacilli in less than 25 per cent; the productivity of such microscopy will be improved if the pellicle which often forms on the top of the cerebrospinal fluid specimen is stained and examined.

Culture will eventually be positive for M. tuberculosis in 75 per cent. Of the cerebrospinal fluid abnormalities, only the degree of pressure elevation has prognostic import, higher pressures being associated with a tendency to early deterioration owing to brain stem herniation. Accordingly, the fluid should be removed cautiously and very slowly, especially when the pressure is over 300 mm. of water.

Tuberculous Meningitis Treatment and Prognosis.

Therapy should always include isoniazid and streptomycin except when coexisting renal insufficiency complicates the use of the latter. In this case, another effective drug, e.g., ethambutol or rifampin, may be substituted for streptomycin. Early in the course, isoniazid should be administered in larger than conventional dosage (8 to 12 mg. per kilogram in the adult, and 15 to 20 mg. per kilogram in children). If response is favorable, these dosages may be reduced, respectively, to 5 mg. per kilogram and 10 mg. per kilogram after four to eight weeks. Pyridoxine (100 mg. per day) should be administered during the period in which increased isoniazid dosage is administered.

Isoniazid is usually given as a single oral daily dose, but this may be replaced by intramuscular administration of an equal total dose, usually in two or three divided doses, if oral therapy is not possible. The drug diffuses well into the subarachnoid space (see Chronic Pulmonary Tuberculosis —Isoniazid). Streptomycin dosage is 1 gram daily in adults and 0mg. per kilogram in children, given as a single injection.

Before isoniazid became available, streptomycin, which is transferred poorly across the blood-brain barrier, was often administered by intrathecal injection, but with such marked toxic effects, principally deafness, that this route is no longer acceptable or recommended. Streptomycin may be safely reduced to administration every other day or be replaced by PAS after three or four months of treatment with favorable response. When clinical symptoms have been absent and the cerebrospinal fluid normal for six months, it is reasonable to continue with isoniazid alone for a total course of two to three years.

Bacteriologic cure should be achieved in three fourths or more of the patients. However, this does not prevent the development of permanent neurologic residua such as weakness, paralysis, 6/incfness, or deafness, other cranial nerve palsies, hydrocephalus, compromised intelligence, and, rarely, symptoms and signs of pituitary or. hypothalamic dysfunction such as precocious puberty, obesity, diabetes insipidus, and panhypopitui: tarism. These complications are thought to belocal consequences of the inflammatory response, and accordingly adjunctive therapy designed to alter this response might have great advantage.

The use of intrathecal tuberculin in the hope of favoring the resolution of the basilar hyperplastic exudate has been tried, but this treatment has never been generally accepted. Use of corticosteroid hormones or corticotrophin has received much wider acceptance. Although evidence is conflicting, most studies reveal a slight but definite survival advantage in groups receiving adjunctive corticosteroid therapy, particularly in prevention of early deaths from brainstem herniation, presumably owing to the ameliorating effect of these agents on cerebral edema.

The response to corticosteroid therapy is often dramatic, with rapid clearing of sensorium, regression to cerebrospinal fluid abnormalities, defervescence, and loss of headache. Even if the long-term beneficial effects are slight, this prompt symptomatic improvement is thought to justify corticosteroid therapy .’‘”Accordingly, prednisone in dosage of 60 to 80 mg. per . day is recommended in all cases of tuberculous meningitis complicated by any alteration in sensorium, neurologic abnormality, evidence suggestive of subarachnoid block, or cerebrospinal fluid pressures in excess of 300 mm. of water. This will obviously include most cases. Therapy may be tapered rapidly in the second or third week to a level of 30 mg., and thereafter decreased at a slower rate every third or fourth day, using the signs and symptoms of meningeal inflammation as a guide in the dosage reduction. If these recur, dosage should be elevated again. Usually steroids can be entirely discontinued after six to eight weeks.

Recovery in patients treated with isoniazid- containing regimens should approach 75 per cent. Infancy, old age, associated active tuberculosis, severe neurologic abnormalities, and high (over 300 mm. of water) cerebrospinal fluid pressures are unfavorable prognostic factors. One quarter of cases will demonstrate some permanent neurologic residuum, although usually this will not be disabling.

Tuberculomas.

Tuberculomas, once the most frequent cause of intracranial mass lesions in children, are now very rare. Except in cases in which meningitis develops because of extension to the subarachnoid space, the symptoms are those of an expanding cerebral or cerebellar mass. Diagnosis is usually made at surgery. Antimicrobial therapy should be administered when the diagnosis is made, both in the hope of some resolution and to prevent the development of meningitis after operation