Based on the Language Map of the Language and Book Development Agency, of the 668 languages spoken in the territory of the Republic of Indonesia, there are 68 regional languages spoken in the Kalimantan region. With so many regional languages, in certain areas in Kalimantan it is possible that we will have different mother tongues with our neighbors on the right, left, front, or behind our houses. The existence of Indonesian which is the national language of Indonesia or the language (Malay) Banjar which is the language of association or lingua fraca in several provinces in Kalimantan makes speakers of the 68 mother languages able to communicate well because there is a language that makes them have mutual understanding.

Imagine, when religious propagators such as scholars and missionaries in the 17th to 19th centuries came to Kalimantan to spread their religion, what language should they use for that purpose? The existence of the Malay language (which later became the Indonesian language) and the Banjar language (Melayu) became one of the ways to communicate with speakers of the 68 different regional languages. Therefore, the use, development and spread of the Malay language in the archipelago, including in Kalimantan, cannot be separated from the spread of religion, including the spread of the Gospel by missionaries.

In the archipelago, the spread of the Bible began with the translation of the Bible into Malay as the lingua franca around the 1600s. Then, the Bible was also translated into other Nusantara languages, such as Javanese, Toba Batak language, and Ngaju Dayak language which is one of the regional languages in Kalimantan. Although the Bible and later the Bible used the local language, Malay was still used.

This paper describes how the use of the Malay language which later became the Indonesian language in spreading the gospel in the archipelago, especially in Kalimantan. This picture is obtained by looking at the history of translating the Bible into Malay as well as other Indonesian languages and the role of the church in Kalimantan in the use of Indonesian.

The data in this paper is the result of literature study and interviews with the Kalimantan Evangelical Church (GKE) congregation as a representative of regional churches in Kalimantan. The data were analyzed to obtain a chronological description of the use of Indonesian in the spread of the gospel in Kalimantan.

B. Translation of the Bible into Malay and Other Archipelago Languages

In “History of the Indonesian Bible”, Sabda Foundation ( http://sejarah.sabda.org/) states that the Gospel of Matthew was first translated into Malay by a bilingual named Albert Cornelisz Ruyl in 1612 and published in 1629. It is a bilingual book, namely Malay and Dutch. Then, Ruyl translated the Gospel of Mark in 1638. Jan van Hasel translated Luke and John which was published in 1638. Overall then the Bible was translated by Daniel Brouwerios in 1668. Melchior Leijdecker, who is the pastor of the Malay-speaking congregation in Batavia, translated the complete Bible in language High Malay from 1691 to 1701. Because of the High Malay language, the Bible is difficult for users of Low Malay to understand. The Bible was later revised by Caludius Thomsen and then by Benjamin Keasberry into Malay to make it easier to understand with the help of Abdullah bin Abdul Kadir Munsyi. This book was printed in Latin script and Malay Arabic script (Jawi) in 1875.

Elsewhere, Hillebrandus Cornelius Klinkert also revised Leijdecker’s translation by adapting it to the Malay dialect used in Java, namely Low Malay, in 1861 (Klinkert’s translation of the Bible was reprinted in 1949). However, because his Malay language was considered too lowly, Klinkert was moved to Tanjung Pinang in Riau to improve his High Malay language skills. Then, he translated the Bible into High Malay and completed it in 1879 before returning to his country and becoming a lecturer in Malay. In addition, there are other translations used in the Malacca Peninsula and Singapore.

Before the pledge of the Youth Pledge was pronounced in 1928, in addition to High Malay and Low Malay, the Bible / Bible had been translated into languages in the archipelago, including Javanese, Batak Toba and Dayak Ngaju. In 1820, Gottlob Bruckner completed his translation of the New Testament into Javanese. In Sumatra, in 1885, Nommensen completed the translation of the New Testament into the Toba Batak language. In 1846, Johann Friederich Becker, August Friederich Albert Hardeland, Timotheus Marat (a Dayak Ngaju), and Nicodemus Tomonggong Joyo Negoro translated the Bible into the Dayak Ngaju language.

The translation of the Bible into the Dayak Ngaju language is closely related to the spread of the gospel in Kalimantan. Johan Heinrich Barstein, a German missionary, departed from Batavia and arrived in Banjarmasin for the first time in 1835. He followed the Barito River, then the Kapuas River, then settled in an area on the banks of the Kapuas River. The area is a Dayak Ngaju speaking area. The first local-language Bible in Kalimantan was a direct translation from Hebrew into the Dayak Ngaju language. However, in Kalimantan, the Gospel is not only conveyed to the Ngaju Dayak speaking people. To the Dayak sub-tribes who do not speak Dayak Ngaju, the evangelists use the Malay Bible.

C. The Role of the Church in Kalimantan in the Use of the Indonesian Language

The existence of a church in Kalimantan cannot be separated from the Kalimantan Evangelical Church (GKE). One hundred years after the arrival of German missionaries – followed by missionaries from Switzerland – to Kalimantan, the Dayak Evangelical Church (GDE) was born in 1935. The church’s birth coincided with the placement of five Dayak priests to several areas in Kalimantan. The church, which originally had a tribal concept, later turned into a regional church with the name Kalimantan Evangelical Church in 1950, five years after Indonesia’s independence.

The existence of the Bible in the Dayak Ngaju language in Kalimantan did not eliminate the role of the Malay language at that time. The people of Kalimantan are ethnic communities who have their respective sub-ethnic languages. Therefore, the Bible in the Dayak Ngaju language cannot be used, except for the Ngaju Dayak people. It was Malay or the Indonesian language that later played a role in evangelizing other Dayak sub-tribes and also became the language used by GDE / GKE. Ukur (2002: 262) states that the 1935 document “Dayak Evangelical Church Regulations” he found only in Dayak Ngaju, Dutch, and German. However, in fact in the life of the congregation, other documents such as holy bath testimony or baptismal certificates are found in two languages, namely Malay and Dutch. Church documents after Indonesia’s independence,

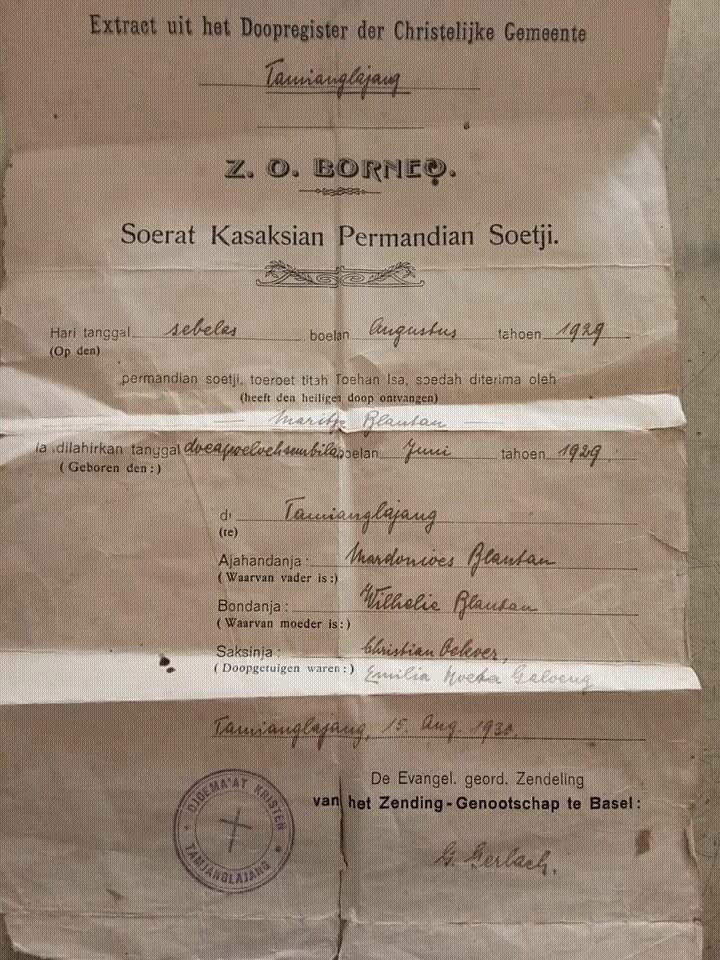

Figure 1 The Holy Bathing Letter, 1930

This shows that the documents used in church life are Indonesian-language documents.

The Klinkert Malay translation of the Bible is also widely used in Kalimantan due to the limited mastery of the other Dayak sub-tribes over the Ngaju Dayak language. In the Maanyan-speaking areas inhabited by the Dayak Maanyan sub-tribe in Tamiang Layang and its surroundings, the Indonesian (Malay) Bible is used. Certain translations of the Bible into the Maanyan language were used much later.

Church congregants who have lived in the Kalimantan Evangelical Church area since the 1950s said that when they were little, the liturgy or rituals of worship in their area used Indonesian. At Sunday School (worship or religious activities for children) Indonesian and a few local languages are used. When the people who live in an area are people who understand the same sub-ethnic language, the neighborhood worship in the houses of the congregation is carried out in rotation in the local language, but with Bible reading and hymns in Indonesian. In Tamiang Layang itself, the Maanyan language neighborhood house worship was carried out until the 1990s. When the division of the region became a district and many immigrants who could not speak Maanyan there, society becomes multiethnic as well as multilingual. Environmental worship was also carried out in Indonesian.

D. Conclusion

By looking at the history of the translation of the Bible into Malay as well as other Indonesian languages and the role of the church in Kalimantan in the use of Indonesian, it can be concluded as follows.

- The spread of the gospel in the archipelago in the 1600s was carried out using the Malay language which was the language of association and commerce at that time. Until two centuries later, Malay became the main language in spreading the gospel. The use of the Malay language remains dominant even though there were Bible books in the Dayak language sub-tribe in the mid-19th century.

- After Indonesian independence, the use of the Indonesian language became stronger in the life of the church in Kalimantan, which is reflected in the absence of a Dutch equivalent in church documents.

- The Indonesian language is widespread due to its use in church life in Kalimantan in a multiethnic and multilingual society. Indonesian is used in church documents, books, and in worship rituals in addition to the use of certain Dayak sub-ethnic languages.