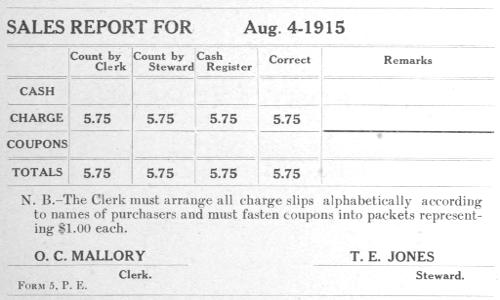

After the day’s business is over, each clerk gathers up all his receipts for the day and assorts them into three piles, representing the cash, coupon and charge sales, respectively. He then makes out his sales report on Form 5 as shown in Fig. 4. This report should be printed on the face of an end-opening envelope measuring not more than 4¼ × 10 inches, thus forming a convenient receptacle for the coupons, charge slips and cash turned in. The printed form should be, say, 7½ × 3 inches. As these envelopes are not subjected to rough usage, being used but once, any kind of cheap paper will serve the purpose. It might be well in certain cases to have the envelopes match the color of the original charge sales slips for that department, but ordinarily, this would be found an unnecessary refinement. After making out this sales report, the clerk places in the envelope the cash, coupons, etc., and hands it to the Post Exchange Officer or to the Steward, if so authorized. (For obvious reasons, the Exchange Officer personally should receive and check the receipts the night of pay-day and at intervals during the month, even if the Steward is ordinarily authorized to do so.) The Steward or Cashier has meanwhile unlocked the cash register, noted the readings of the record wheels and taken out the tape showing the printed record of sales.

Figure 4. (Reduced in size)

Now, assuming that triplicate records are used, the Steward takes the triplicate copies—either book or roll—“throws” them or checks them for[12] numbering, to see that all are accounted for, and totals their value on the adding machine. By comparing this total with that shown by the appropriate wheels of the cash register, he ascertains if all charge sales have been rung up. If these two agree, all is well, so far. If they do not agree, a note is made of the discrepancy for use in connection with the operations hereafter described.

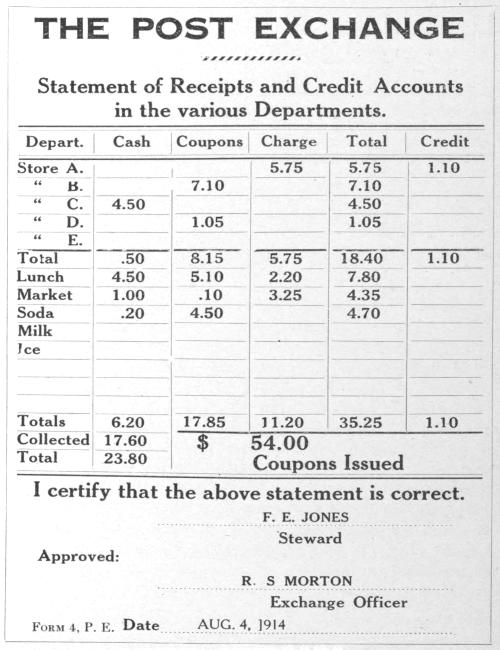

Figure 5, (Reduced in size)

By this time, the clerks should be ready to hand in their reports and receipts. The Steward fills out the rest of Form 5 as called for by the various columns and abstracts these reports to his Form 4 as shown in[13] Fig. 5. This form should be printed on a card measuring 3½ × 8⅜ inches, to permit convenient filing. If printed on thin paper, it will have to be filed on a Shannon file which is not so convenient in the long run. These cards should be of fairly good stock, as they are a part of the permanent records of the Exchange, but should be no heavier than necessary. The Steward carries down the totals on Form 4 and compares them with the three separate totals shown by the cash register. Restricting ourselves to a discussion of the charge sales, we see that if the total of the triplicate slips, the totals of the clerks’ reports and the total shown by the cash register all agree then the charge sales statement shown on Form 4 is correct. If there is any discrepancy in this or any other column of Form 4 the mistake should be found and corrected before the clerks are dismissed for the night. Suppose, for example, that the cash register shows a total of $20.60 charge sales for the day and the total on Form 4 is $21.90. The first step is to have the clerks make sure that their reports correctly state the actual amount of charge sales slips turned in. If they are correct, then some clerk has probably forgotten to ring up one or more sales. To trace the fault, let the Steward read off all the charge sales from the record tape of the cash register, calling off at the same time the letter of the clerk who rang up each sale. These can be compared with the triplicate copy of the sales slips, or the assembled clerks can be required to note the sales accredited to them, the grand total of which must equal $20.60. In this manner, the error is definitely located. On the other hand, suppose the cash register shows $21.90 and the total on Form 4 shows $20.60. The effect is that produced by a clerk being short $1.30 in charge sales slips after he has actually made the sales. The same procedure as before will locate the mistake. If he cannot produce the slips (or cash or coupons as the case may be) or satisfactorily explain the mistake, the clerk in error should be required to make good the discrepancy. Discrepancies in cash and coupons can be located and remedied in the same manner. It is important that the clerks be required to participate in the task of locating mistakes and to make good on errors, otherwise there will be no incentive to careful work.

When the totals of the clerks’ reports check against the cash registers, the next step is to check the former against the receipts in cash, coupons and charge sales slips actually turned in by the respective clerks. The cash should, in fact, be counted immediately upon being turned in, checked O. K. on the clerks’ reports and put in a safe place. The charge slips handed in by each clerk are compared with the strip from the adding machine (on which the clerk has added up his slips before making out his report) checked against the report and put aside for filing. Coupons are handled in the same way except that they are sealed in the envelope and put in a[14] secure place until the Exchange Officer personally can burn them. This matter of destroying coupons should never be delegated to any other person. In view of the fact that the receipts turned in by each clerk should, and usually do, check exactly with his report, this particular routine is recommended, as it allows the dismissal of the clerks before commencing the work described in this paragraph. In case of mistakes, the simple expedient of making the clerk at fault assist in the work for a few evenings, is usually sufficient to prevent a repetition. In large Exchanges, where the coupon and charge sales are large, it is not customary to total the charge sales slips and count the coupons until the next morning. If the receipts turn out to be greater than called for by the reports, the surplus can be taken up by entering on a single line of Form 26 (described hereafter), whenever the books are closed (or oftener, if desired) an item showing what departments are credited with these excess coupons, exactly as if it were another day’s transactions. Such entry should, however, be prefaced by the words, “excess coupons”. Shortages should be collected from the clerk at fault, thus making the reports correct. The Exchange Officer should occasionally make the coupon and the charge sales counts himself.

It would be unbusinesslike, if the coupon or charge sales are heavy, to require the Exchange Officer, the Steward or any other high priced man to waste his time counting coupons or any other similar task. A less expensive employee should be detailed for this purpose. For such unskilled labor, a boy at $10.00 per month who can run errands, etc., would be a profitable investment in many cases, thus leaving the expensive employees free to do more important work.

Too much stress cannot be placed upon the importance of insuring the correctness of the data entered on Form 4. If the above mentioned checks have been applied, there should be no trouble in any phase of our charge accounts.

Daily Summary of Charge Sales.

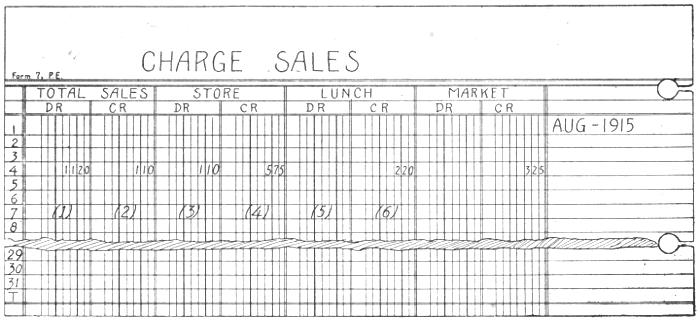

Figure 6. (Reduced in size)

For various self-evident reasons, we use Form 7, shown in Fig. 6, for showing a month’s charge sales. This form gives us in a most convenient shape, a summary of that part of our (daily) Forms 4 that relates to our charge sales business, it safeguards us against the loss of any Form 4 and facilitates posting our ledger accounts. This form is kept up to date, the charge sales from Form 4 being entered thereon daily, and therefore, affords us a most efficient aid in closing our books at any moment. At the end of the month, or whenever the books are closed, we find the totals of the columns of Form 7 and post these totals as lump sums into the ledger. For example, the total of column 1 is posted as a debit in the ledger against[15] Bills Receivable, Customers; the total of column 2 as a credit to the same account. The total of column 3 should be posted as a debit against the Store account in the ledger, this being for articles returned to the store by our customers; the total of column 4 is posted as a credit to the store account, being for articles sold from same, etc. These sheets, constituting Form 7 are 11 × 14 inches, and cost $1.75 per hundred without printed headings; a sectional post binder to fit them can be bought for $3.75. The sheet is the same on both sides and will, therefore, take care of seven departments if we use the whole width of the open book. This will be found ample in most cases. It is useless expense to have the headings, etc., printed on the sheets, because a single sheet with neatly written headings can be made to serve as a sort of index for a great many sheets, provided they are mounted above it and are trimmed off just below the headings “DR.” “CR.”, and also trimmed on the outside margin so that the date figures on the lowermost sheet will serve as an index to the lines of the upper sheets. This labor and money saving point will be more fully discussed later.

Recording Charge Sales Slips.

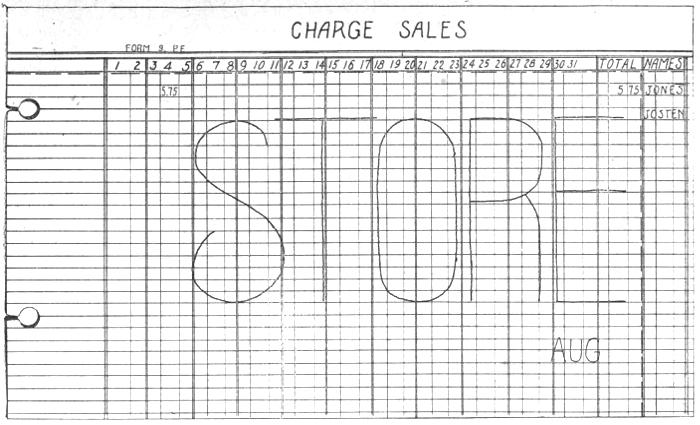

After these slips have been checked against the clerks’ reports, they must be sorted out and filed according to the names of the purchasers. For this work, have two card index drawers, each fitted with a set of guide cards marked on the tabs with the names of our charge customers. As each slip is found, file it behind the proper name. We first take all the “Store” slips and file them in this manner; we then go through this “sorting drawer” and total the slips belonging to each customer and enter these totals in the column representing that date on Form 9, (see Fig. 7) opposite the names of the respective customers. At the same time, we insert the sales slips diagonally in their proper places in the other or permanent filing drawer. The total of these entries on Form 9 should equal the total charge sales credited that date to the Store on Form 7. If it does, the slips that have been placed diagonally can be shoved down into the proper places as we are through with them; if it does not, they can easily be removed for further examination. This daily check should invariably be made for each department. We proceed in like manner with respect to the other departments, each department having its own sheet or sheets like Form 9. It is evident that this form gives us a summary of all the charge sales made each day from each department, showing the amounts sold to each of our customers. At the end of the month, each line is added across and the total entered. The “Total” column is then added up and compared with the total obtained by adding together the figures[17] (representing the daily totals) on the bottom line. If these two totals check against each other and against the total shown on Form 7, the account may be considered correct and is a record of the daily transactions between our customers and the department considered.

Figure 7. (Reduced in size)

The book in which we bind our Form 9 is known as the “Charge Book”, and it may be well to explain here the physical make-up of this important book of record. It is, of course, on the loose-leaf principle, being of the type known as a “sectional post binder”. It costs $2.50 and the ruled sheets (without special printing) cost $1.00 per hundred. It is, however, to the manner of handling the sheets of the book that attention is especially invited. The old fashioned way would be to enter the names of our customers down the left hand margin of each sheet until all were entered, put the name of the department and the month and year at the top of the sheet and the days of the month at the tops of the successive columns with the heading “Total” at the right of the sheet. Thus, if we had five departments and enough credit customers to require six sheets for the list, we should have to prepare thirty sheets in this manner every month. Now, to show how we can eliminate unnecessary work by the exercise of a little forethought, let us assume that we have started our record in this manner. Now take six copies of Form 9, trim them along the heavy broken lines shown in Fig. 7, and bind one of these sheets in front of each of those we have previously prepared. It is obvious that the book is now ready for another month’s entries without any preparatory writing or numbering whatever other than labelling each new sheet in some convenient place with the month and department to which it pertains. Of course, to care for the five departments, we should have to do this for all five sets of sheets that we originally prepared. It follows that, provided our list of customers does not change, this same operation of inserting trimmed sheets would constitute the only labor necessary to continue this record for an indefinite period.

After considerable experimenting and actual trial in service, the following described scheme has been evolved for handling this record in an efficient manner. While no claim is made that it is perfect, it is believed that it will give thorough satisfaction wherever it is given a fair trial and will save many hours of labor in keeping the books.

1. Take a sheet, Form 9, and enter the names of your charge customers in alphabetical order, commencing on a left hand page. To allow for future changes, leave a blank line before each name and one or two blank lines at the bottom of the page for sub-totals, etc. For clearness and permanence, these names should be put in from a black “record” typewriter[19] ribbon. Write in the headings of the various columns as shown on Form 9. The object in placing the “total” column near the outside margin is to have it next the customer’s name, thus minimizing the chances of error in taking out the wrong total when we make our postings at the end of the month.

2. If our list of charge customers will require more than one sheet, take another Form 9 which we shall call Sheet No. 2 and proceed in a like manner, using the same side of the sheet as before. This should be repeated until all our charge customers are entered. Several blank lines are left at the bottom of the last sheet. Thus, when we have finished and have inserted the sheets in our book, we shall have a complete list of our charge customers all recorded on the left hand pages of our book, that side of each sheet that forms the right hand pages of our book being blank.

3. Now, in order to utilize these blank pages, thus avoiding unnecessary waste, we proceed as follows:—Open your book between Sheets 1 and 2; page 1 will then be on the left and page 2 on the right. This page 2 should now be prepared in a manner exactly similar to that used in preparing page 1, except that the customers’ names are on the right hand margin with the total column next inside. This is clearly shown in Fig. 7.

4. Prepare the blank sides of the other sheets in a similar manner and we shall then have two complete lists of our charge customers, one occupying the left and the other the right hand pages of our book, the confronting pages being practically symmetrical.

5. Let us assume that the Exchange has five separate departments in which charge sales can occur. We cut five sheets along the heavy broken lines shown in Fig. 7 and insert them between pages 1 and 2. Five more trimmed sheets are inserted between sheets (whole sheets) 2 and 3, and so on for the rest of the book. In order to identify these sheets if accidentally removed from the binder and to facilitate the making of entries, we print on each of them in large letters, the name of the department and the month to which they refer. This is best done lightly with red ink as shown (in black) in Fig. 7 where the sheet is marked STORE—AUG. This red ink lettering will not obscure the black ink figures subsequently made.

6. Let us agree to use the left hand pages for the first month’s account and the right hand pages for the next month’s account. Let us take the first trimmed sheet and mark it “STORE—JAN” on one side, and “STORE—FEB” on the other. Do similarly for the sheets reserved for the “market”, “lunch room”, and other accounts. The sheets containing the[20] typewritten headings are not used for recording sales, but are used for guide sheets, for reasons to be set forth later.

It is easy to see from the preceding description that our charge book is a running account, and being always up to date, can be closed at short notice. When two months’ records have been entered, the trimmed sheets are lifted and filed, as will be described hereafter. Fresh trimmed sheets are again inserted in the proper places and the record proceeds as before.