Anthrax is an infectious disease of wild and domesticated animals caused by Bacillus anthracis. Occasionally it is transmitted to man. A necrotic ulcer of the skin or mucous membranes is the most common feature of the disease, but hemorrhagic mediastinitis and disseminated infection with hemorrhagic meningitis may also develop. Depending upon the most prominent feature of the disease, anthrax has been variously referred to as malignant pustule, splenic fever, woolsorters’ disease, milzbrand, and charbon.

Etiology.

Bacillus anthracis was identified in 1849 by Davaine, and was further characterized by Koch in 1877. It is a gram-positive, spore-forming, encapsulated, hemolytic, aerobic micro-organism. It resembles B. subtilis and B. cereus but can be differentiated from these organisms by its virulence for laboratory animals such as the mouse and

rabbit, by its lack of hemolytic activity on blood agar, and by lysis of B. anthracis with specific bacteriophage. In broth, the bacillus elaborates an antigen that can be used for specific immunization (“protective antigen”). The spores of B. anthracis are killed by boiling for ten minutes but survive for long periods of time in soil, in animal carcasses, and following aerosolization.

Epidemiology.

Anthrax has occurred sporadically and in epidemics throughout the world. Cattle, sheep, goats, horses, and swine are most commonly found to have anthrax; outbreaks of the disease in these animals rarely occur in the United States. Although the disease has been acquired by butchering, skinning, or dissecting infected carcasses, human infection in the United States is observed almost exclusively in persons handling imported contaminated hides, wool, goat hair, or other animal products. There has been a progressive decrease in anthrax in the United States in the past several years (17 cases from 1956 to 1964). The infection may be transmitted to man by direct contact, inhalation, and ingestion of infected material.

Pathology and Pathogenesis.

Anthrax is characterized by edema, hemorrhage, necrosis, and various degrees of inflammation. B. anthracis possesses a glutamyl polypeptide capsule that interferes with phagocytosis, and this contributes to its pathogenicity. The gelatinous edema of anthrax infection’ contains large amounts of bacterial capsular material. The serum of many animals has lytic activity against the bacillus, but this anthracoid substance seems to bear little, if any, relationship to natural resistance. It is probable that B. anthracis initiates infection in the skin only through abrasions, cuts, or other types of injury. During the course of lethal anthrax infection in laboratory animals a bacterial toxin is produced that is responsible for death. This lethal toxin can be neutralized by specific antitoxin.

Clinical Manifestations.

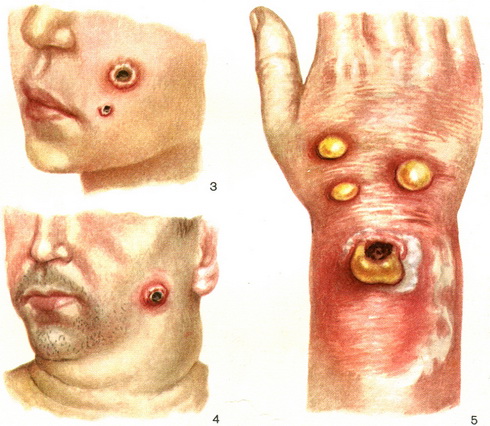

The skin lesion of anthrax usually begins as a small erythematous papule that becomes vesicular, necrotic, and covered with a dark crust or eschar. Intense nonpitting edema, which may not be erythematous, often surrounds and may extend a considerable distance from the eschar. Characteristically the lesion is pruritic but not very tender or hot. The skin lesion is commonly on exposed areas of hands, arms, neck, or face; and there may be mild regional lymph node enlargement. Lymphangitis is not usually observed. Constitutional symptoms and fever are frequently absent unless the skin disease is severe or the infection becomes disseminated, when high fever, prostration, and death may occur.

Infrequently anthrax may develop without a lesion, possibly following inoculation into the skin, but probably more commonly following inhalation of spores of the bacillus in contaminated air. Characteristically, this form of anthrax is severe and is associated with disseminated infection. Hemorrhagic mediastinitis, often without pneumonia, and hemorrhagic meningitis may occur. Death is common in this form of anthrax; the illness may begin abruptly, be of short duration/and terminate rapidly. Dyspnea and cyanosis are . indicative of respiratory or ventilatory insufficiency. Roentgenographic examination of the chest in inhalation anthrax reveals widening of the mediastinum. Leukocytosis is ordinarily not pronounced. Pleural effusion may complicate pulmonary anthrax. Anthrax in man from ingestion of bacilli is rare.

Diagnosis.

. Anthrax is most readily diagnosed in persons known to have been exposed to animals or animal products potentially contaminated with B. anthracis. Cutaneous anthrax can be differentiated from many other bacterial infections of the skin by the insignificance of regional adenopathy, lymphangitis, and cellulitis in relation to the severity of the eschar and edema. Furthermore, pruritus, lack of tenderness, and intense nonpitting edema are characteristic of anthrax. Small skin lesions, however, may be more difficult to recognize. Pulmonary anthrax can be identified by a history of occupational exposure and acute widening of the mediastinum shown by roentgenographic examination. Anthrax, meningitis is confused with subarachnoid hemorrhage or cerebrovascular accident, but is usually associated with prominent signs of infection, and gram-positive bacilli can be seen in the cerebrospinal fluid.

In disseminated anthrax infection, blood cultures are often positive. Occasionally, the bacilli may be identified in the centrifugal sediment of blood treated with 3 per cent acetic acid solution and stained with Wright’s stain.

In cutaneous anthrax, the bacilli can usually be cultured from the lesions, or typical encapsulated bacilli will be seen when stained with a polychrome eosin-methylene blue stain (Wright or Giemsa). Their direct cultivation on peptone agar should always be attempted. If the specimen has to be shipped, the specimen should be dried on silk threads or on a sterile glass slide.

of the occurrence of anthrax-like bacilli on the skin, it is imperative that diagnoses be confirmed by animal inoculations, preferably in guinea pigs or mice or by specific bacteriophage lysis. In pulmonary anthrax, the bacillus has been found microscopically in the sputum and in the pleural exudate.

Prognosis.

Cutaneous anthrax is often a self limited disease, but dissemination of the infection and death may occur in 20 per cent of patients. A fatal outcome in cutaneous anthrax can be averted by appropriate treatment, but treatment of disseminated infection is often unsuccessful in preventing death.

Being A Doctor You Must Know About Anthrax Treatment.

B. anthracis is susceptible to the action of penicillin and the tetracyclines. Penicillin G should be given in total daily doses of at least 1.2 million units, starting as soon as anthrax is diagnosed or seriously suspected. The effectiveness of the tetracyclines is probably not quite so great as that of penicillin; nevertheless, they are effective in cutaneous anthrax (Figs. 1 and 2), and may be administered in total daily dose of 2.0 grams. Therapy with penicillin or the tetracyclines should be continued for seven days. It should be emphasized that, in patients with disseminated anthrax, the progressive course may be so rapid that antimicrobial drugs may not save the patient’s life.

Prevention.

Anthrax can be prevented in man by control of infected animals or animal products. Sterilization of wool during manufacture is often impracticable, although this is the means employed to prevent infection from clothing and other products, such as shaving brushes, made of potentially infected materials. Vaccination with “protective antigen” is effective in preventing infection in persons likely to be occupationally exposed.